|

|

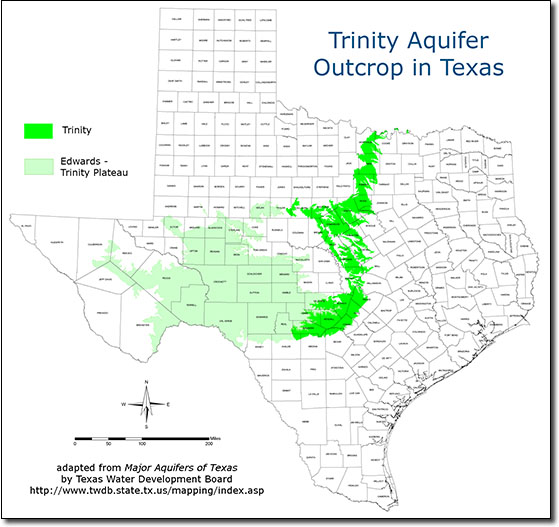

The Trinity Aquifer The Trinity Aquifer extends in a band through the central part of the State from the Red River to the eastern edge of Bandera and Medina counties, and the Trinity-Edwards Plateau Aquifer covers all or part of over 20 counties from Gillespie to the trans-Pecos region of west Texas. Together, they are the primary water source for most of the Hill Country. Most users in northern Bexar, Bandera, Kendall, Comal, and Kerr counties get their water from the Trinity. At the same time, all of Bandera, most of Kerr and Kendall, and large parts of Comal and Bexar counties serve as drainage or catchment area for the Edwards Aquifer. So even though users in the Hill Country use a different aquifer they are caught up in Edwards Aquifer issues, especially with regard to restrictions on development or discharges that could affect the quality of water that eventually ends up as Edwards recharge. There is also growing evidence that hydraulic connections between the Edwards and the Trininity aquifers are more significant than previously believed, and this may eventually have additional implications for Trinity Aquifer use and management.

Unlike the Edwards, the Trinity Aquifer recharges very slowly. Only 4-5% of water that falls as rain over the area ends up recharging the Aquifer, and water also moves through the Trinity much more slowly than through the Edwards. The Trinity contributes a significant amount of water as recharge for the Edwards. Recharge to the Edwards can occur where the layers are juxtaposed by faults or, where the Trinity underlies the Edwards, by upwelling. A finite-element model built by Eve Kuniansky and Kelly Holligan in 1994 suggested that perhaps as much as 360,000 acre-feet per year enters the Edwards from the Trinity. A study in 2000 suggested this figure, which amounts to more than half of Edwards recharge, is probably too high, and placed the value at 59,000 acre-feet (Mace, 2000). An analysis in 2011 concluded that interformational flow is very difficult to characterize and measure, but it is probably more than suggested by Mace (Green, 2011). There are actually several aquifers that make up the Trinity. The Trinity is a group of geologic deposits divided up into several distinct formations, and each formations is in turn comprised of several layers called members. In North Texas around Dallas-Fort Worth, the upper formation is the Paluxy. By the 1970s water levels in the Paluxy had been drawn down by as much as 550 feet, so many wells in that area have been abandoned in favor of surface water supplies. The Paluxy does not occur south of the Colorado River, where the upper unit is the Glen Rose formation. This is the formation that users in south central Texas are most familiar with, and it has also been overused in many places. It is comprised mainly of limestone that thickens toward the Gulf, and it is divisible into upper and lower members. Below the Glen Rose formation, the lower units of the Trinity Group are the Twin Mountains and Travis Peak formations. The Twin Mountains formation occurs in north-central Texas and is the most prolific of the Trinity aquifers. Toward the south in the Hill Country, the Travis Peak formation is made up mostly of sands, silts, conglomerates, and limestones, and it is subdivided into members as shown below. Most of these lower members of the Travis Peak formation have not been extensively used. Water quality in the Trinity Aquifers is generally much lower than in the Edwards and it is also more variable. For example, in north-central Texas waters in the Glen Rose are highly mineralized and are a source of contamination for wells drilled into the underlying Twin Mountain formation, but towards the south in the Hill Country the Glen Rose can yield moderate quantities of fresh water.

These photos, taken in 2007 in the newly formed Canyon Gorge, illustrate why drilling a well in the Trinity can be a hit-or-miss undertaking. On the left, notice how fractures in the limestone tend to form in straight lines and at right angles. These become solutionally enlarged and form well-defined underground conduits such as shown at right. They can be so geometric and regular they almost look like man-made irrigation trenches, but they are not. When drilling a well, you might hit one or several of these conduits, or you might not. If you don't, you end up with a dry hole. These conduits were exposed suddenly during the flood of 2002, not slowly by erosion, so they offer an especially instructive look at the typical underground structure (see the Canyon Lake section for more on Canyon Gorge).

A recent model developed by the Texas Water Development Board projects steep drops in well levels over the next 50 years for large areas overlying the Trinity Aquifer (2). Already, many users have seen their wells go dry and are having to deepen them to search for more water. For many users, the model pointed out the need for regional planning and diversification of their water source. The cities of Boerne, Fair Oaks Ranch, and some other smaller Hill Country communities have already contracted with the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority to receive water from Canyon Lake. You can retrieve a copy of the report here. Exploding growth over the Trinity and dwindling supplies have stirred concern about regulation of this resource. In 1990, the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission designated the Trinity region to be a Priority Groundwater Management Area (PGMA), defined as an area where a critical water shortage is occurring or can be expected to occur in the next 25 years. Inclusion in a PGMA gives county officials some authority to regulate development over the Aquifer by requiring that developers prove there is water available before platting new construction. It can also aid in the formation of a groundwater conservation district, which would have taxing and regulatory power and could regulate well spacing and production. In March 1999, a group of residents began outlining a plan to create such a district. In September 2000, the TNRCC scheduled a hearing to hear arguments for and against including the portion of northern Bexar county that lies over the Trinity in the Priority Groundwater Management Area (5). This area kind of slipped through the crack. It was not included in the PGMA originally because it was under the jurisdiction of the Edwards Underground Water District. But the EUWD was dissolved and replaced by the Edwards Aquifer Authority, which does not have authority to regulate the Trinity. On April 6 2001 the House Natural Resources Committee approved legislation to create a groundwater management district in northern Bexar county to oversee withdrawals in that area (6).

In the late 1990s, the situation regarding rules and regulations for much of the Trinity Aquifer was much like what existed for the Edwards Aquifer prior to Senate Bill 1477, which regulates Edwards groundwater withdrawals (see Rules Section). The "rule of capture" still prevailed in the rest of the State outside the Edwards region, so there were few restrictions on using groundwater or drilling wells in the Trinity Aquifer. But lawmakers had come to recognize the rule of capture is basically an unworkable free-for-all, because it gives everyone unlimited rights to a finite resource. It is sort of like a circular firing squad. Even so, none had been willing to tackle the issue head on, and you can't really blame them. In Texas, politicians who dare to suggest that private property rights are less than paramount are routinely placed on rails and escorted from town wearing tar and feathers. So in 2001, the Legislature punted by passing a law that makes it easy for property owners to form Groundwater Conservation Districts (GCDs) by petition. It gave such Districts the authority to regulate spacing and production from wells, and deemed GCDs to be the State's preferred method of groundwater management. This provided a politically correct frame of "local control" for pumping regulations while allowing lawmakers to avoid certain political doom. Since 2001, the number of such districts in Texas has more than doubled to almost 120 (in October 2011). All the Districts participated in a process in which local residents determined the "Desired Future Conditions" (DFCs) for their aquifer. A Desired Future Condition is a quantifiable future groundwater condition, such as a particular groundwater level, a level of water quality, or a volume of spring flow. Most of the time, the Desired Future Conditions will involve pumping limits. In April 2001, the first pumping limits for the Trinity were established by the Headwaters Underground Water Conservation District, which has the power to regulate withdrawals in Kerr county (8). The rules only apply to high-volume wells, mostly those used in irrigation. For wells that are capable of producing more than 25,000 gallons per day, the rules establish a cap of 137 gallons per day per acre of land for Middle Trinity Aquifer wells, and 178 gallons per acre per day for Lower Trinity Aquifer wells. Water planners and officials who imposed the rules felt the move was a bid to make the resource sustainable for generations to come. In May 2001, the election of Water District and City Council candidates who were most outspoken about protecting the Trinity was interpreted as a public validation of the new rules (12). In February 2000, the San Antonio Water System signed a contract to buy Trinity Aquifer water from the Massah Development Corporation. The company owns the Oliver Ranch, located west of US 281 just south of Bulverde Rd. Under the 10 year contract, the company drilled several wells to supply up to 4,500 acre-feet of water to San Antonio. SAWS extended pipelines to the point where it can accept the water, and will also maintain the wells and pay Massah $1 per 1,000 gallons of water, up to $3.25 million per year (1). In September 2000, the SAWS Board approved a contract to drill wells on another property nearby owned by BSR Inc.(4). Under this contract, SAWS may purchase about 1,500 acre-feet per year. In Spring 2001, several controversies erupted concerning the Trinity Aquifer and golf courses. Near Bulverde, developers applied for permits from the Southeast Trinity Groundwater Conservation District to drill two new wells and supply 400 acre-feet of water per year to their proposed Cibolo Cliffs Golf Course (7). Nearby residents who had to haul water in trucks to their property in the summer of 2000 when their wells went dry objected to the developer's plans (9). An engineering study suggested the golf courses' wells would not seriously draw down other wells in the area, but neighbors remained skeptical. In April 2001, the District voted to deny a permit that would have allowed the developers to drill two test wells to determine what the effect would be on neighboring wells (11). A second controversy in Spring 2001 involved creation of a tax district for a planned golf resort in Bexar county that partially overlies the Trinity Aquifer. Developers planned to turn almost 2,900 acres into a PGA Village with resort hotels, 3 golf courses, a conference center, retail stores, and low density residential development. A taxing district known as the Cibolo Canyon Conservation and Improvement District No. 1 would be a developer-controlled district with almost all the powers of a city to tax and use the revenues to pay for roads, water, and other infrastructure needs. Water would come from the San Antonio Water System and golf course irrigation would be partially accomplished by reusing wastewater, but there would also be two wells in the Trinity Aquifer that would eventually be used for part of the golf course properties. Some questioned the wisdom of giving developers powers of eminent domain and the power to tax to finance the infrastructure (10). By May 2001, both the Texas House and Senate had approved a bill to create the District, and it was signed by Governor Perry on May 23 (13,14). Details about how the development will be built were to be worked out between the city and the developers, since the property is within the extraterritorial jurisdiction of San Antonio. Although it started as a Trinity Aquifer issue, part of the development also lies over the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone, and by mid-2001 the issue had exploded into what would become one of the most bitter and divisive debates in San Antonio history. By July 2001, nine groundwater districts over the Trinity, including those in Comal, Kendall, Hays, Bandera, Blanco, Gillespie, Kerr, Medina, and Travis counties, had joined the Hill Country Alliance of Groundwater Districts. The Alliance began in 2000 as an informal way for board members of the various districts to share information and talk about common issues. Most members do not favor formation of a Trinity Aquifer Authority for the region, which would be similar to the Edwards Aquifer Authority and have the power to regulate and allocate pumping. Members favor local control and feel an Authority would put control of the water in the hands of water marketers and people who do not have the best interests of the community at heart. In 2001 the Alliance was awarded a $450,000 grant to install nine monitoring wells throughout its nine counties (15). On July 1, 2001, newspaper headlines reported a chemical plume beneath Camp Bullis Military Reservation had contaminated a small portion of the Trinity Aquifer and could pose a threat to the Edwards (16). Decades before, decontaminating fluid was poured over numerous vials of various chemical weapons and buried in trenches. It was thought the decontaminating fluid had broken down over time to form trichloroethene (TCE), which if ingested at high levels can cause a wide range of health problems from nervous system effects to coma and death. A 1999 report by hydrogeologist George Veni outlined several ways the chemical could migrate through the Trinity Aquifer and along fault planes and eventually reach the Edwards; but it also stated that contaminants would probably be diluted to less than drinking water standards by the time they got there. On July 2, 2001, the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission said the threat to the Edwards was "overstated" in the July 1 article, and spokesman Patrick Crimmins said there is no evidence the plume could spread into the Edwards (17). The military has drilled a number of monitoring wells around the site and is planning a thorough cleanup. An undetermined number of private wells around the military installation were also to be tested to determine if the chemical plume had migrated offbase. In August 2001, the Army began distributing bottled water and charcoal filters to a handful of residents after tests revealed that a plume of degreasing solvents had spread from Camp Stanley and contaminated five private Trinity Aquifer wells. Camp Stanley is an armaments facility adjacent to Camp Bullis in far north Bexar county where degreasing using chlorinated solvents was carried out for decades. Contaminant levels exceeded drinking water standards in only one of the wells, owned by the Korean Martyrs Catholic Church. The Army fitted the well with a charcoal filter. Two other wells are owned the Bexar Metropolitan Water District, which shut them down and continued to serve customers from other wells. The two remaining wells were also fitted with charcoal filters. The Army will drill about 40 monitoring wells to try and pin down the location and extent of the groundwater contamination, and the most likely clean-up method will be a pump-and-treat system (18). In October 2001, a rush to drill new wells into the Trinity aquifer in northern Bexar county sparked fears among users in other counties that water levels could decline significantly, affecting wells and property values (19). Between May 2000 and October 2001, more than 150 permit applications were filed with State officials for new wells. Many were hoping to receive their permits before the new Trinity-Glen Rose Groundwater Conservation District could impose fees and regulation. In 2001 the Legislature created the District to manage groundwater in the small area of northern Bexar county that had previously slipped through the regulatory crack, but public water supply wells completed before September 2002 will be exempt from regulation. There is also concern that increasing use from the Trinity could affect recharge to the Edwards Aquifer. Hydrologists believe that up to 10% of Edwards recharge comes from the Trinity. In November 2001, the new District asked Bexar County Commissioner's Court for $78,000 in start-up funding. The District could not exercise it's tax-collecting powers until voters confirmed the District's existence in an election that was held in 2002. District Board members also considered creating a non-profit corporation that could accept donations on behalf of the District (20). Also in November 2001, Trinity users in New Braunfels rejected an initiative to make the Southeast Trinity Groundwater Conservation District permanent. The district was a temporary one created by the Legislature and needed voter approval to become permanent. County Judge Danny Scheel said the defeat was a catastrophe for the county because it allows golf courses and cities to the south to "...drill wells and pump all the water they can out of the aquifer." In defeating the district, opponents had aroused public fears of meters and well-drilling fees. Supporters claimed the opponents were spreading misinformation (21). Elsewhere over the Trinity in November 2001, the board of the Headwaters Underground Water Conservation District denied a rancher's well permit application to pump about 76 million gallons annually into a large stock pond on a Bandera county ranch. Filling stock tanks with wells is a common practice in Texas, but the increasing concerns about overpumping and the large size of the proposed tank drew attention to the application and sparked heated debate. Board president James Hayes said "Our board feels that water in a lake like this is wasteful due to evaporation and seepage, and our rules mandated that we deny the permit." A spokesman for rancher Bill R. Wilson said "We believe the board ignored the law and treated Mr. Wilson's permit request in a discriminatory manner." (22) In December 2001, the city of Garden Ridge completed a well in a productive portion of the Trinity, ensuring a water supply for the city other than the Edwards aquifer. Drilling the well had been a calculated risk. With the Trinity, there is always the chance that wells can be unproductive or water quality can be poor. (23) In February 2002, The San Antonio Water System announced that customers who live and work in far northern San Antonio would start receiving water from the Trinity Aquifer. This marked the first time the city-owned utility had delivered water from any other source than the Edwards. The area that will receive Trinity water is north of 1604, roughly bordered on the west by 281 and on the east by Bulverde Road. In June 2002, the Army released a plan to address the groundwater pollution beneath Camp Bullis that the public learned about in July 2001. So far no trichloroethane (TCE) has been detected in drinking water wells on or off the military reservation, although levels of TCE above drinking water standards have been found in 8 of 24 monitoring wells. The plan calls for allowing the chemicals to disperse and degrade through natural attenuation until more testing and monitoring can determine what steps should be taken as a final remedy. (24) In November 2002 voters overwhelmingly confirmed the creation of the Trinity-Glen Rose Groundwater Conservation District and elected board members. The district planned to initially focus on learning a lot more about the aquifer and developing a resource plan. It will have the power to impose fees on larger wells, regulate pumping, and after voter approval, levy taxes. (25), (26) In May of 2003, Hays county voters approved the creation of the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District, which covers most of the west side of the county, and also elected a board of directors. Opponents said it would simply create a new government bureaucracy, while proponents said it was the only way to preserve the Trinity Aquifer. (27) Also in May of 2003, the new Trinity-Glen Rose Groundwater Conservation District adopted its first major rules and fees, charging businesses and water sellers for pumping from the Trinity Aquifer in north Bexar county. Funds from the fee of 3.07 cents per 1,000 gallons pumped ($10.00 per acre-foot) were to be used to develop a management plan for the Glen Rose. The District also adopted rules requiring wells to be registered. Rules were posted on the agency's new web site at http://www.trinityglenrose.org.(28) Meanwhile, in June of 2003, some residents and officials who live in the area that would have been regulated by the defeated Southeast Trinity Groundwater Conservation District worried their portion of the Trinity Aquifer was becoming more vulnerable to water hogs. (29) Western Comal county is one of the last areas left where users of the Trinity can pump as much as they want, and it is quickly growing and urbanizing. Some fear that San Antonio will exploit the situation, but the San Antonio Water System has a long policy of steering clear of areas where there are are water shortages, according to SAWS' Water Resource Director Susan Butler. "We are absolutely not looking at groundwater from Comal county", she said. It seems more likely that businesses and developers might take advantage of the lack of regulations and establish new wells. By late in 2003, in light of the proliferation of new groundwater conservation districts all over the Texas Hill Country, some water experts had begun to question the wisdom of relying on such entities to manage groundwater. Although they are they state's preferred method, and the idea of 'local control' is an easy sell politically, experts point out they represent a fragmented and inconsistent approach to groundwater management. Each district cares about an area that is pretty much the same size as its border, but the issues are much larger. New districts such as the Cow Creek Groundwater Conservation District, set up to manage the groundwater in Kendall county, have come under fire from citizens who claim the fee structures are inequitable and their duties are redundant. In July of 2003 residents in Kendall county formed the Kendall County Well Owners Association, which questioned the need for the District to exist. (30) By 2008, a full-scale backlash against the Cow Creek District seemed to be in progress, with scores of commercial pumpers openly defying requirements to obtain pumping permits for their wells. In June of 2008 the District said that Tapatio Springs Golf Resort had not obtained well permits and that it was seeking a $10,000 fine for the Resort's failure to submit reports and records under a 2006 District order. Tapatio Springs partner Jay Parker said "we need to figure out if these rules are unreasonable for this community that's been here since 1981. I understand that rules change, but rules can't change and put people out of business." (31) Other users that depend on Trinity wells insist that golf courses are a frivolous waste of precious resources. Cow Creek board member John Kight said "when we get down to these dry times, we can't afford to be watering fairways." In July of 2008, the Cow Creek Board slapped the resort with a $10,000 fine for violations of rules on groundwater pumping, and the Board also alleged the resort had illegally used surface water from a creek for irrigation. District staff was directed to file a complaint with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which oversees and issues surface water pumping and diversion rights. (32) In November of 2008, the cessation of flow at Jacob's Well in Hays county was taken as a sign of the increasing pressure on the Trinity. Jacob's Well is a treasured Hill Country spring-fed swimming hole, where flows have been observed to cease only one time before. David Baker, Executive Director of the Wimberly Valley Watershed Association, said ongoing drought, overpumping, and the spread of impervious cover were the culprits. The springs normally flow over 1,000 gallons per minute and flowed throughout the drought of record in the 1950s. The Assocation called on the county to stop permitting new wells or subdivisions in the area of the watershed that supports Jacob's Well. In adjacent Comal county, Commissioner Jay Milliken said "It's kind of that canary in the coal mine. It's a bellweather of what is coming our way. And what's coming is not very good." (33).

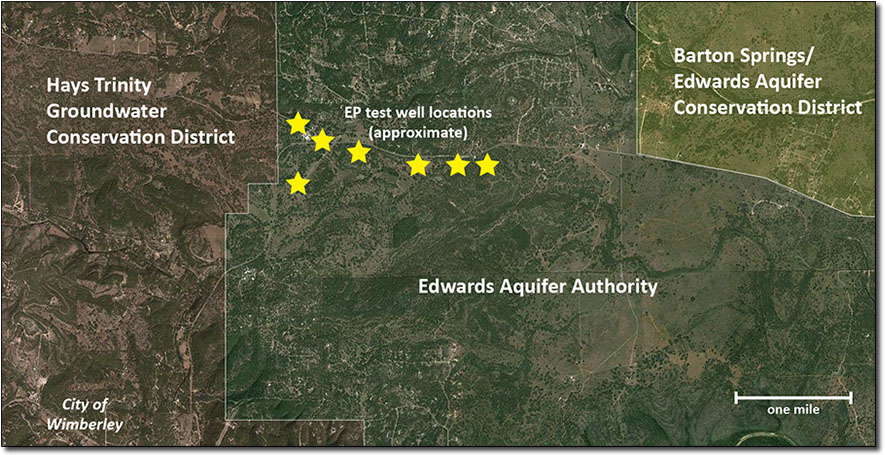

In April of 2009, the Texas Water Development Board completed a groundwater availability model for the Edwards-Trinity and Pecos Valley aquifers, in order to assist in evaluating groundwater management strategies and assess current and future trends. The model includes the Hill Country portion of the Trinity where the main population centers are located. The model suggested that about 60% of total discharge is to streams, springs, and reservoirs, 25% of discharge is to wells, and 15% of discharge is cross-formational flow into the Edwards Aquifer. The model was a challenge to develop and calibrate because of the large study area and complexity of the aquifer systems. As a result, the authors advised it should be used with caution and should only be used for assessing groundwater availability on a regional scale, not for specific locations or wells (Anaya and Jones, 2009). In July of 2010, the board of the Groundwater Management Area voted to limit depletion over the next 50 years to no more than 30 feet below the current average water level. Some permit holders and others concerned about maintaining spring and stream flows had argued for a zero drawdown, but concerns about meeting demand for existing permits and future growth won out. The Bandera County River Authority and Ground Water District had advocated for a 10-foot drawdown, but the Cow Creek Groundwater Conservation District argued that a 10-foot drawdown would force a revision of some existing permits it has issued. (35) The debate served to point up the complete mess that has resulted in Texas from the proliferation of groundwater districts, each with its own interests, and each seeking to independently manage a common resource. Another debate that started in 2010 also served to point up the inadequacy of local groundwater districts as a means to regulate a regional resource. Comal county is one of the fastest growing in the state, but users in the western part of the county have twice voted down the creation of a Groundwater Conservation District. So what does the state do if it gives a "local control" party and nobody comes? In 2010 the TCEQ initiated litigation to add western Comal county to the neighboring Trinity-Glen Rose GCD. Hearings were held before the State Office of Administraive Hearings, and the plan was to hold a final trial-like "hearing on the merits" before TCEQ's three-member commission, which would vote then vote on whether to force creation of a groundwater district or take other action to protect the aquifer. After vocal local protests, it granted an "abatement period" and suspended those proceedings to give residents time to consider whether to create a district on their own (36). Stakeholder groups began meeting to decide whether to have a third referendum on creating a district, and opinions varied widely. Some were dismissive of forecasts of impending water shortages and said the state should respect the two votes already taken. Stakeholder Mike Maurer, Sr., complained "They are now coming in and threatening us, 'If you don't do this, we're going to force one on you.' ". At the other end of the spectrum, GCD advocate Jay Millikin pointed out that because they don't have a GCD, residents don't have a vote in long-term regional water planning and that "People are making decisions about allocating surface and groundwater resources without us being involved in it." In the 2013 legislative session, State Rep. Doug Miller filed House Bill 3924, which would have formed a Comal Trinity GCD upon voter approval, but it failed to pass. When the abatement period expired on July 1, 1013, TCEQ Executive Director Zak Covar asked administrative law judge Paul D. Keeper to resume the hearings process because efforts to resolve the issue “both legislatively and locally have not been successful. The parties have had ample time to resolve the matter without need for a hearing", Covar said. He asked Keeper to schedule a preliminary hearing sometime between July 15 and August 23 to determine which parties are still interested in pursuing the matter, to align the interested parties into groups if possible, and to set a procedural schedule (37). In December of 2014, Comal County Commissioners approved a resolution asking the county's legislative delegation to try again at forming a Groundwater Conservation District in the State Legislature. A bill was proposed that would give Comal County Commissioners the power to appoint seven members, and it would also eliminate a requirement that local voters confirm the new District. Previous proposals provided for an elected board and required confirmation by voters (38). In June of 2015, Comal county finally got a Groundwater Conservation District when House Bill 2407 became law without the Governor's signature. County Commissioner Scott Haag explained "We didn't get a signed bill, but it wasn't vetoed. You might say it was uncontested. We got it accomplished." The new district does not have authority to levy taxes and will be funded by production fees from wells, ranging from $1 per acre-foot for small farm and ranch wells to $40 per acre-foot for bigger production wells (48). By the end of July 2015, Comal county commissioners had appointed seven inaugural board members who immediately got busy establishing the new entity. One of the appointees, rancher Larry Hull, said "Having a district is a good approach to conserving water and educating the public. It also gives us membership in GMA 9. Until this point, Comal county has not had voting representation with that group." (49) The Electro Purification controversy In January of 2015 a new Trinity Aquifer controversy erupted over plans by a Houston-based firm called Electro Purification to pump and sell up to 5.3 million gallons of water per day to the city of Buda and two utility districts, the Goforth Special Utility District which serves the Niederwald area, and the Anthem Municipal Utility District, which would serve a planned subdivision near Mountain City (39). The wellfield would be located in an area of Hays county near Wimberley that historically had not been presumed to be within a Groundwater Conservation District that regulates the Trinity Aquifer, so pumping was governed only by the rule of capture. Although a representative for Electro Purification told Hays county commissioners the company's pumping would not harm the wells of nearby residents, those residents had deep concerns. A report prepared by LBJ Guyton for the legal firm Braun & Gresham estimated that if Electro Purification produced 5.3 million gallons per day for one year, water levels near the wells would decline over 500 feet. See the LBJ Guyton report. The controversy highlighted several deficiencies in the approach that Texas applies to management of groundwater. Perhaps foremost among these is the rule of capture itself, which may be tested by the upcoming court case we will discuss shortly. It is hard to find any experts these days who don't believe the rule of capture is fully outdated. Even the Texas Supreme Court, in a 1999 decision, recognized it is "harsh" and "outmoded", but it declined to change the law at that time. In an open letter, Hays County Commissioner Will Conley wrote that Texas' rule of capture is insufficient to manage commercial water producers. "The rule of capture should not be the only rule that applies to a corporate entity with the intentions of commercial distribution of water resources," he wrote. "I believe there must be some accountability on this whole process beyond free market principles that will protect the private property rights of land owners in an impacted area." The other deficiency highlighted by the controversy is the patchwork regulatory system that Texas applies through groundwater conservation districts. Such districts are the state's preferred method of groundwater control, and normally an area can only be in one such district.

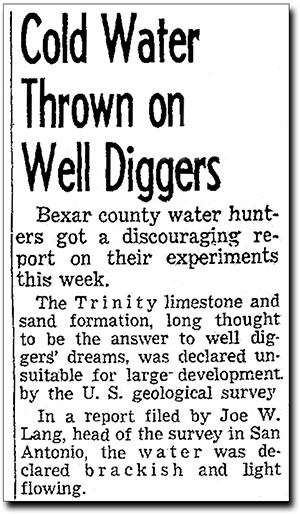

This area in question here was within the jurisdiction of the Edwards Aquifer Authority, but that agency only asserts control over the one layer of limestone that is the Edwards, not the underlying layer that is the Trinity. Just to the east of the site is the Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, but that agency also does not assert or claim jurisdiction over wells in the Trinity. Just to the west and north of the site is the Hays-Trinity Groundwater Conservation District, and whether or not the site is in their jurisdiction appears to be another subject of a court battle we will examine shortly. The agency's own map of their jurisdictional area appears to show it is not under their control (see their map). A GIS analysis by Robin H. Gary of the Barton Springs district estimated there are 1,589 groundwater-supplied properties within two miles of the Electro Purification test wells (see the analysis). Meanwhile, nobody really believes any of these various limestone formations are completely separate and unconnected. In recent years we have learned a lot about interconnections between the Edwards and the Trinity, and about connections between the San Antonio and Barton Springs segments of the Edwards. Yet the regulatory structure in Texas accounts for none of this. Buda did not delay, however. On January 20, the Buda City Council heard from a parade of concerned citizens and officials, added provisions that require mitigation of impacts on local wells, and then voted 6-1 to sign a contract with Electro Purification. Three days later more than 200 people packed the Wimberley Community Center for a meeting of the Hays-Trinity Groundwater Conservation District, hoping to hear of strategies to regulate or stop the project. What they heard was not encouraging. The District could try to annex the portion of the Trinity where the Electro Purification wellfield is proposed, but it would be difficult and may require legislative action, and even if successful the District is simply broke. It has no taxing authority or even the ability to charge groundwater production fees. (41) By mid-February, tensions in the area were rising even further. Buda Mayor Todd Ruge told an Austin news station he had been receiving threats, and Wimberley residents organized a "Boycott Buda" campaign, pitting neighbor against neighbor. "Save Our Wells" bumper stickers began appearing on cars all over Wimberley. (42), (43) On February 25, the Wimberley Valley Watershed Association announced the formation of a new non-profit group, the Trinity Edwards Springs Protection Association, or TESPA. A press release said it was formed as a response to the Electro Purification proposal, but that it intended to address issues that go beyond the pumping dispute to include more general protection for springs throughout central Texas. One of the founders of the group was noted environmental attorney Jim Blackburn. The press release also said the group intended to file suit. (44) See press release. Within weeks, TESPA had filed a petition in Hays county asking a court to issue a temporary injunction stopping any drilling or pumping and maintaining the status quo until the larger issues could be decided, which could easily take years. One of the arguments made is the area is within the jurisdiction of the Hays-Trinity Groundwater Conservation District by default, because no other agency is regulating the Trinity in Hays county and "The Legislature evidenced an intent that all groundwater in Hays County be protected by a groundwater conservation district." The petition asserts the defendants have failed to comply with the mandatory permit requirements required by the Texas legislature through the District, and it asked the court to halt all activity until permits are obtained. See original petition. The petition also asked that if injunctive relief cannot be provided under the section of the Texas Water Code that provides for Groundwater Conservation Districts, the court provide that relief by applying a doctrine of "reasonable use", also known as "the American rule". This doctrine is generally thought to be almost the opposite of the English common law "rule of capture" that prevails where no Groundwater Conservation District has jurisdiction, but the petition points out that even in the 1904 court case that established the rule of capture, the decision hinged on the defendant making a "reasonable and legitimate use" of the water it took from under its land. "Thus, the foundation upon which the rule of capture rests in Texas, actually is a foundation which already recognizes reasonable use." The petition also points out that since 1904, the rule of capture in Texas has been modified or limited many times, and the entire paradigm of regulating using Groundwater Conservation Districts employs a "reasonable use" doctrine. For these reasons, the petition asserts the rule of capture "is a tattered remnant of the original rule causing more harm than good." The petition urges the court to recognize "the rule of capture is no longer defensible, and in fact is dangerous public policy as it risks exhaustion of critical water resources." Meanwhile, on the legislative front, State Representative Jason Isaac of Dripping Springs and State Senator Donna Campbell filed a flurry of bills aimed at stopping the Electro Purification project. One bill was to expand the territory of the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District to include the wellfield and a second bill would do the same for the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District. Lawmakers recognize that only one bill can pass because an area can only be in one district but they elected to apply a "shotgun" approach. A third bill would limit the eminent domain powers of the Goforth Special Utility District, making it probably unable to build a pipeline. (45) When the bills were heard by the House Natural Resources Committee on March 24, they ran into harsh criticism from other lawmakers. Committee vice-chairman Trent Ashby of Lufkin said Electro Purification is "not violating any laws here. They're playing by the rules." The most controversial bill was the one that would strip the Goforth District of its eminent domain powers, but it was the Legislature itself that gave it those powers and the lawmakers said they were reluctant to set a precedent of taking away powers they had given. (46) All three bills were left pending in committee (47), which usually means they advance no further, but supporters campaigned hard using social media and email alerts asking people to contact legislators directly. In May of 2015, a decision by the Texas Supreme Court to let stand a lower court ruling was interpreted by legal experts as extremely favorable to the position of Electro Purification. (47) In that case, the lower court ruled that a taking occurred when the Edwards Aquifer Authority limited the ability of pecan farmers Glenn and JoLynn Bragg to pump water from under their land. Read about that case on the Laws and Regulations page. In June of 2015, the efforts of the Save Our Wells crowd paid off when House Bill 3405 became law without the Governor's signature. The contested area was added to the Barton Springs-Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, and persons who had planned projects will get a chance to demonstrate their pumping will not cause a failure to achieve Desired Future Conditions or cause unreasonable impacts on existing wells. The law requires that persons operating a well or who have entered into a contract must file a permit application and will be given a temporary permit for an amount up to the production capacity of the well. A regular permit will then be processed and the authorized amount could be reduced if the applicant can't prove that Desired Future Conditions will be met and there will be no unreasonable impact on existing wells. Get HB 3405 here. In September of 2015 the Texas Tribune noted that HB 3405 might not actually thwart pumping plans by Electro Purification, because an "unreasonable impact" is a subjective standard and nobody really knows what it means. Conservation District General Manager John Dupnik said "What does 'unreasonable impact' mean? We don't know. We've got to work through it. Any time you see the term 'unreasonable', that's where the attorneys really get excited, right?" Even so, residents and local officials who succeeded in getting HB 3405 passed remained confident the science would demonstrate an unreasonable impact and EP would ultimately get less water than it asks for. (50) In October of 2015, EP asked for almost nothing - it applied for a permit to pump 100 acre-feet annually from the Trinity, or about 89,000 gallons per day, which is a small fraction of the 5.3 million gallons per day envisioned. (51) It was not clear if EP had abandoned its plans or if this was part of a legal strategy. In March of 2016, the Barton Springs-Edwards Aquifer Conservation District began a formal rulemaking process as part of their new responsibility to manage the area that legislators added to their district with the 2015 legislation. The District noted that proposed rules would focus on management strategies that will protect existing wells and preserve the long-term availability of water supplies from the Trinity Aquifer. Under the proposed rules, applications for large-scale groundwater projects would require more rigorous aquifer testing, an expanded public outreach area, and continued aquifer monitoring. "These rule changes would establish a framework to allow for a science-based evaluation of prospective applications, assess the potential for unreasonable impacts to existing wells and the aquifer, and require the necessary measures to avoid those impacts," said District General Manager John Dupnik. (52) By June of 2016 the District had processed about 20 applications for existing wells that were required to obtain a permit, and it had issued Regular Production Permits to all but one. Low capacity wells that produce from the Trinity Aquifer and are used only for domestic purposes are exempt from having to obtain a permit. Mr. Dupnik said his District was actively working on building relationships with residents in the newly regulated territory. He said a lot of effort had been put into organizing outreach sessions to give residents access to the District and to inform them on what BSEACD does. (53) On May 27, 2016 the Texas Supreme Court issued a ruling that may have implications for TESPA and efforts to limit pumping from the Trinity. The Court ruled that Texas' "accommodation doctrine" should also apply to groundwater, in addition to oil and gas. Under this doctrine, owners of underground mineral rights such as oil and gas must accommodate the activities of whoever owns the surface estate. This means, for example, that surface landowners now have a specific legal doctrine on which to challenge plans to pumpwater from below their property. And so some observers hailed the decision as a major victory for landowners. Others were not so positive, because the ruling also establishes the rights of groundwater owners are dominant over those of surface owners. The groundwater owners now have an explicit and expansive right to access the surface tract without the permission of the surface owner and without compensation. Also, the burden of proof under the accommodation doctrine is very high and falls on the surface landowner. In the Texas Tribune, Austin water lawyer Vanessa Puig-Williams noted that landowners must not only prove that drilling operations will substantially impair their existing use of the land and that there are no reasonable alternatives, but they must also prove that reasonable alternatives are available to the producer. Historically, it has been difficult to meet that burden in oil and gas drilling disputes. "The accommodation doctrine is really not that protective of the surface owner's interests," she said. (54) In July of 2017, Electro Purification submitted a scaled-back application to pump up to 2.5 million gallons per day, down from the original 5.3 million. In October of 2017 another company's plans to increase its pumping from the Trinity raised concerns among nearby residents. Texas Water Supply Company, which already sells water to San Antonio Water System, partnered with a New York private equity firm Brightstar Capital Partners to expand sales to others. Brightstar senior partner Raul Deju said "We have a lot of existing wells and we have a lot of capacity." A news release stated that wells controlled by Texas Water Supply Company could produce up to 32,000 acre-feet per year. Deju said the company could ramp up to that level of production "within the next eight years." Officials with the Trinity Glen Rose District expressed concerns about the proposal in a letter. It said "The proposed withdrawal now makes it much more difficult, if not almost impossible, to manage this resource effectively. We realize this has an impact not just to our district, but has the potential to impact all within the area." Deju said "We operate by the book. I'm an environmentalist at heart. We're going to operate these wells appropriately, adequately and in accordance with all laws and regulations." Meanwhile, SAWS officials said they have found the water from the company to be unreliable. SAWS President and CEO Robert Puente said "Buyer, beware, because that Trinity is very unpredictable. Well, actually, it is predictable. In a drought, you can't rely on it." (55) In May of 2018, Electro Purification was back in the news when the BSEACD announced a 20-day comment period on the company's application. About 100 residents gathered at Blue Hole Regional Park in Wimberley to protest the application. The BSEACD general manager and staff recommended a five-year, multi-phase ramping up of production and monitoring of any potential negative impacts on the Aquifer. In Phase I the company would pump 273,750,000 gallons per day, in Phase II 1.0 million gallons per day, Phase III 1.5 million gallons per day, and Phase IV 2.5 million gallons per day. General Manager Kirk Holland said "The board would ultimately be hard pressed to say, 'you can't produce groundwater under your property, or leased property.' We need to look at what provisions could allow for pumping in a way that protects the resources of other people that have private property rights in the area." (56,57,58) By June of 2018, opponents had sprung back into action and filled the Wimberley Community Center for an informational session on the details of the proposed water production permit. Resident Tom Sosebee said "We thought it was behind us, that EP wasn't going to happen. Here we go again." (59) At their July 10, 2018 meeting, Hays County Commissioners unanimously supported a resolution to support contesting the proposed permit. (60) Changing views of the Trinity In 1953, the Trinity Aquifer was deemed unsuitable for large development. Researchers from the United States Geological Survey found the water in all the wells they investigated was brackish and light flowing, and their laboratory analysis of the water quality found it was unsuitable for public supply. Fifty years later, even extremely low-yielding members of the Trinity group, such as the Upper Glen Rose formation, are seen as playing a big role in meeting the future demands of fast-growing counties. Other small Hill Country aquifers mentioned in 2013 as contributing to future supplies were the Ellenberger, Hickory, and Marble Falls aquifers. All of them have been deemed "nonrelevant" for regional planning purposes, but some now want them included in future supply inventories.

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Materials used to prepare this section: Texas Water Development Reports 195, 235, 269, 273, 345, 353, and 373 are available online at the TWDB's Groundwater Reports Page. Anaya, Roberto and Ian Jones, (2009). Groundwater Availability Model for the Edwards-Trinity (Plateau) and Pecos Valley Aquifers of Texas. Austin: Texas Water Development Report No. 373, April 2009. Ashworth, John B and Hopkins, Janie. Major and Minor Aquifers of Texas. Austin: Texas Water Development Report No. 345, November 1995. Ashworth, John B. Ground-Water Availability of the Lower Cretaceous Formations in the Hill Country of South-Central Texas. Austin: Texas Water Development Report No. 273, January 1983. Beach, James and Kristie Laughlin, (2015). Hydrogeologic Evaluation of Proposed Electro Purification, LLC Project in Hays County, Texas. Austin: prepared for Braun and Gresham, Attorneys At Law, March 2015. Klemt, William B., Perkins, Robert D., and Alvarez, Henry J. Ground-Water Resources of Part of Central Texas with Emphasis on the Antlers and Travis Peak Formations, Vol.1. Austin: Texas Water Development Report No. 195, November 1975. Kuniansky, Eve L., and Holligan, Kelly Q. (1994). Simulations of Flow in the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer System and Contiguous Hydraulically Connected Units, West-Central Texas. Austin: US Geological Survey, Water-Resources Investigations Report 93-4039. Mace, Robert E., Ali H. Chowdry, Roberto Anaya, and Shao-Chih (Ted) Way. Groundwater Availability of the Trinity Aquifer, Hill Country Area, Texas: Numerical Simulations through 2050. Texas Water Development Board Report No. 353, September 2000. Nordstrom, Philip L. Occurrence, Availability and Chemical

Quality of Ground Water in the Cretaceous Aquifers of North-Central Walker, Lloyd E. Occurrence, Availability and Chemical Quality of Ground Water in the Edwards Plateau Region of Texas. Austin: Texas Water Development Report No. 235, July 1979. (1) "SAWS adding 2 supply sources"

San Antonio Express-News, February 16, 2000.

|

||||||||||||||||